Editor Stew note: this is the promised second installment of the Mel and Soren trip to Panicale. You can feel them enjoying the sunshine and basking in the little moments that make a trip worthwhile. Love the words and pictures they paint here. I think it is safe to say they are open and friendly people, and that, as usual, our “home town” responded in kind and made them feel fully at home.

Editor Stew note: this is the promised second installment of the Mel and Soren trip to Panicale. You can feel them enjoying the sunshine and basking in the little moments that make a trip worthwhile. Love the words and pictures they paint here. I think it is safe to say they are open and friendly people, and that, as usual, our “home town” responded in kind and made them feel fully at home.

See you in Italy,

Stew Vreeland

——————————————————————————————-

DOORS, SLOPES & WALKERS

PANICALE, Umbria, Central Italy–I was bought up in a house with two external doors – a front door and a back door. This was, and is still, a fairly substantial house, but these two doors seemed to provide for all of the entrances and exits required during my seventeen years there. The house and its plot offered little that would perplex someone attempting a set of architectural drawings: two floors each identical in dimensions and seated neatly on top of each other; in addition, a flat, rectangular garden to the front, and a flat rectangular garden of double the proportions at the rear.

The architects and builders of Umbria however, appear to have adopted a rather different approach. Showing disdain for the vast flat areas that we look down upon, Umbrians preferred the challenge of creating towns on the insanely steep and dramatic slopes of its rocky hills.

This has had a number of repercussions that take some getting used to for those accustomed to the flat lands of East Anglia. The first is the dizzying amount of doors that an Italian home requires to offer access and exit. Casa Vreeland in Panicale offers seven doors that give access to and from the outside world. Now those of you that are used to the normal front and back door approach might be visualising a property with so many doors lined up across its frontage so that it appears like a row of changing rooms at an old fashioned lido. However, only when you are here can you see why such a multitude of doors are necessary.

Properties in Panicale are not built on simple, level poured concrete slabs. Where foundations for a common house may involve a bit of half-hearted scraping with a digger and a couple of goes on a cement mixer, the Panicale house required huge triangular buttresses of rock and brick, sections of rock cut away here and added there, to provide what seems like a set of treads in a staircase on which they can then start building houses. This means that the upstairs and downstairs parts of a house in Panicale feel like they are in different parts of town. The lowest doors of the property at the back give out onto the street, as do the doors of the intermediate floor. What those of you not familiar with Umbrian hill towns might not grasp is that the street level of the front is about twenty feet above the street at the back.

Properties in Panicale are not built on simple, level poured concrete slabs. Where foundations for a common house may involve a bit of half-hearted scraping with a digger and a couple of goes on a cement mixer, the Panicale house required huge triangular buttresses of rock and brick, sections of rock cut away here and added there, to provide what seems like a set of treads in a staircase on which they can then start building houses. This means that the upstairs and downstairs parts of a house in Panicale feel like they are in different parts of town. The lowest doors of the property at the back give out onto the street, as do the doors of the intermediate floor. What those of you not familiar with Umbrian hill towns might not grasp is that the street level of the front is about twenty feet above the street at the back.

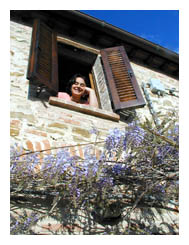

This means that when you are in one part of the house – that is to say, when you roll out of bed, bustle to the bathroom and brush your teeth, looking out of the bathroom window – you meet your neighbour opposite, watering his tomato plants in his basement-level garden. “Ciao”. For those reserved Englishmen, conducting a conversation in your boxers with a man holding a watering can is a new experience. I think this explains why Italians are so socially adept: in your utility room you look across and talk to your neighbour slicing onions; in your kitchen you exchange greetings with a lady returning from the butchers; in your basement you look out and catch sight of someone directly across from you attempting to adjust their roof-top aerial.

As well as this easy conviviality the vertiginous pavements offer a challenge to the walker. The elderly appear to have so many advantages here – the proximity and care of family and the indulgence and care of shop and bar owners to name but a couple – but surely those steep slopes must be a fighting challenge? Well no. Panicale’s streets are softened by a number of expertly positioned and sensible adaptations. The first is the little benches that occur every twenty yards or so. Noticing that progress is becoming demanding, you stop. As you sit you catch up with an old friend making the opposite journey. Rested, you make a bid for your next staging post. The bottega, which despite fighting a daily challenge to cram all their wonderful stock into their tiny shop (taking up valuable floor space) is a chair provided for the tiring walker. Here you can sit and catch up and find out Panicale’s latest news. Now that you have reached the highest point it is a gentle stroll down to Bar Gallo and more hospitality.

As well as this easy conviviality the vertiginous pavements offer a challenge to the walker. The elderly appear to have so many advantages here – the proximity and care of family and the indulgence and care of shop and bar owners to name but a couple – but surely those steep slopes must be a fighting challenge? Well no. Panicale’s streets are softened by a number of expertly positioned and sensible adaptations. The first is the little benches that occur every twenty yards or so. Noticing that progress is becoming demanding, you stop. As you sit you catch up with an old friend making the opposite journey. Rested, you make a bid for your next staging post. The bottega, which despite fighting a daily challenge to cram all their wonderful stock into their tiny shop (taking up valuable floor space) is a chair provided for the tiring walker. Here you can sit and catch up and find out Panicale’s latest news. Now that you have reached the highest point it is a gentle stroll down to Bar Gallo and more hospitality.

The elderly Italian may also call on a family member to help them on the hotter days. It is one of the most moving and balletic examples of filial loyalty and care I have ever seen. Every evening if you sit yourself in Bar Gallo you will see two figures coming down the steep slope towards you. He blind, and head bowed, with only the top of his linen cap showing, she patiently and gently offering a supportive arm.  But this is no sad, stumbling shuffle – this dancing duet glide down with grace and style. Much in the way a metronome swings this way and that, so this couple tilt to the right as their right foot moves out, and as it is planted, their tilt is cushioned to a halt and shifted direction as now the left foot makes its step forward. So with the unnerving rhythm and certainty of a clock’s pendulum they cover the cobbles with the grace of ice-skaters. Beautiful.

But this is no sad, stumbling shuffle – this dancing duet glide down with grace and style. Much in the way a metronome swings this way and that, so this couple tilt to the right as their right foot moves out, and as it is planted, their tilt is cushioned to a halt and shifted direction as now the left foot makes its step forward. So with the unnerving rhythm and certainty of a clock’s pendulum they cover the cobbles with the grace of ice-skaters. Beautiful.

Still Soren

UMBRIA, 45 DAYS TO GO—

UMBRIA, 45 DAYS TO GO—

Back now, really am working. See Stew work. Work. Work. Work. Clean. Clean. Clean. LUNCH TIME! Work. Work Work.

Back now, really am working. See Stew work. Work. Work. Work. Clean. Clean. Clean. LUNCH TIME! Work. Work Work.  Before settling down to nine o’clock frozen food from a bag (Philistine Dinner of Champions-Italian Division) I was taking out the last bag of rubbish. And I could see the tail end of the sunset casting a fragile pink haze to everything in its path. On my way, I met Dily and she had seen me admiring her new apartment. It has a balcony right above a restaurant’s big wisteria covered outdoor dining area. Well, that was a sea of violet in full flower. I had actually seen that before. What I had never noted before was the roses climbing up her wall, up out of the wisteria and headed for the roof. Yellow roses growing right up her balcony. To the top of the fourth floor. It is in the castle walls proper so there is yet one more floor to go. But still. This is a serious bouquet of roses. As we stood there, holding our black plastic bags, the lights twinkled on in amongst the clouds of wisteria and the green arch of neon spelling R.I.S.T.O.R.A.N.T.E. over the entrance blinked on and that put finish to the day. I don’t care what the other tourists were doing, I had a fine time of it. I may have worked even a bit too hard as you can see, I’m just a shadow of my former self.

Before settling down to nine o’clock frozen food from a bag (Philistine Dinner of Champions-Italian Division) I was taking out the last bag of rubbish. And I could see the tail end of the sunset casting a fragile pink haze to everything in its path. On my way, I met Dily and she had seen me admiring her new apartment. It has a balcony right above a restaurant’s big wisteria covered outdoor dining area. Well, that was a sea of violet in full flower. I had actually seen that before. What I had never noted before was the roses climbing up her wall, up out of the wisteria and headed for the roof. Yellow roses growing right up her balcony. To the top of the fourth floor. It is in the castle walls proper so there is yet one more floor to go. But still. This is a serious bouquet of roses. As we stood there, holding our black plastic bags, the lights twinkled on in amongst the clouds of wisteria and the green arch of neon spelling R.I.S.T.O.R.A.N.T.E. over the entrance blinked on and that put finish to the day. I don’t care what the other tourists were doing, I had a fine time of it. I may have worked even a bit too hard as you can see, I’m just a shadow of my former self.